World War I

North East Folk Remember The War.

"There's going to be a war!"

June, 1914, and a young Christian Watt Sim from Broadsea was at Balta Sound, Shetland, one of the hundreds of girls who had travelled up from the mainland to gut herring at the start of the summer season. They stayed in wooden huts near the shore, accommodation arranged for them by John Ewen, the curer who had signed them on for the herring season. Some of the girls would take wall paper with them to decorate their 'huttie' and make the place as homely as possible.

The Archduke of Austria was assassinated in Sarajevo and the German herring traders' ships left the Shetlands in haste. In the mad rush they took every herring, unbranded and all. Many curers were made bankrupt by the Germans and Russians who never did settle their accounts for that year. We waited anxiously for news as the papers came off the steamer. The fishing boats were advised to go home and the sailors on the "Ringdove" were given instructions to make ready for action. The steamship company asked the driftermen to take the coopers home with them to make room for the mass evacuation of the girls. Scottie's Andrew came round on the Friday morning shouting, "Come on you quinies, get packed up as quick as possible. There's going to be a war!"

The Archduke of Austria was assassinated in Sarajevo and the German herring traders' ships left the Shetlands in haste. In the mad rush they took every herring, unbranded and all. Many curers were made bankrupt by the Germans and Russians who never did settle their accounts for that year. We waited anxiously for news as the papers came off the steamer. The fishing boats were advised to go home and the sailors on the "Ringdove" were given instructions to make ready for action. The steamship company asked the driftermen to take the coopers home with them to make room for the mass evacuation of the girls. Scottie's Andrew came round on the Friday morning shouting, "Come on you quinies, get packed up as quick as possible. There's going to be a war!"

Crammed aboard the "Earl of Zetland" we all felt a great sense of relief as the ship cast off and slipped past Huney Island and into open water. We boarded the "Saint Rognvald" at Lerwick, and the ship was absolutely jam packed. I had never seen a ship so crowded. Even the sheep and cattle pens were occupied by girls! We sat high up, beside the funnel as we knew it would be warm there in the cold of the night. As we sailed between the land and the island of Mousa, a mannie and a wifie waved to us from their doorway. I didn't know it then, but I was waving goodbye to Shetland forever.

We thought of submarines as our ship ploughed through the Moray Firth. Dozens of navy ships sailed close by us and the sailors all waved and cheered. They were bound for Invergordon and Scapa Floe. That was the last voyage we made across The German Ocean. It became the North Sea soon after that.

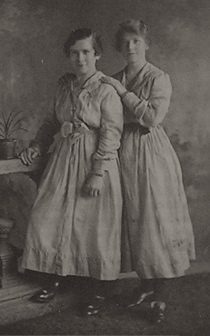

Christian with her pal Christian Noble, 'Bengie's Kirsten,' photographed in 1916 in the uniforms they wore for work in the Keiller's factory in Dundee, packing parcels of sweets for the men abroad, 'Ceylon Toffees and Chocolate Gingers for the officers and boiled sweets and Ju-Jubes for the common soldiers'.

Christian with her pal Christian Noble, 'Bengie's Kirsten,' photographed in 1916 in the uniforms they wore for work in the Keiller's factory in Dundee, packing parcels of sweets for the men abroad, 'Ceylon Toffees and Chocolate Gingers for the officers and boiled sweets and Ju-Jubes for the common soldiers'.

Broadsea, two years later . . .

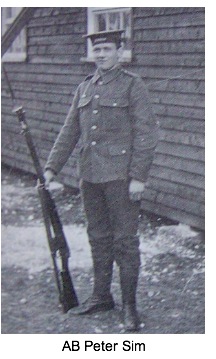

A telegram arrived one morning, another real shocker. My brother Peter, who had gone all through the Dardanelles, had been killed at the Somme on November 13th, 1916. His arm had been almost severed and was due to be amputated but Peter died on his way to the dressing station. Four years later a small package arrived from the War Office. It was Peter's wallet. The army had been searching for bodies for reburial and had found my brother. The note with it said that it had been "found on a fallen comrade".

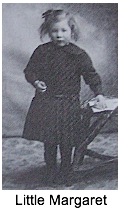

The wallet was mouldy and contained a letter from my sister and two photographs; one of little Margaret, our niece, and one of Albert Watt, a second cousin from New York who Peter had met up with in France. The photos had been four years in his grave.

The wallet was mouldy and contained a letter from my sister and two photographs; one of little Margaret, our niece, and one of Albert Watt, a second cousin from New York who Peter had met up with in France. The photos had been four years in his grave.

Extracted from "A Stranger On The Bars", the memoirs of Christian Watt Marshall of Broadsea.

"Gordons and Barkers"

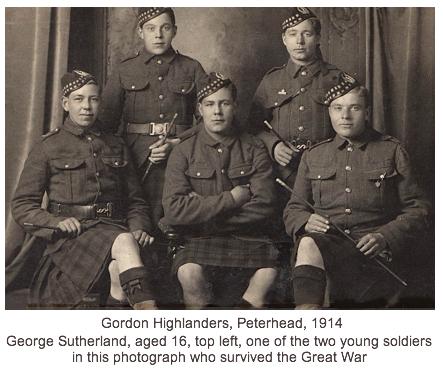

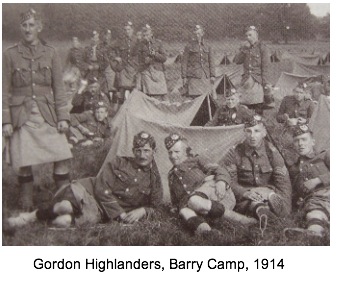

The contrast of experiences during the First World War could not have been greater for my grandfather and grandmother. Granddad, (George Sutherland, Peterhead, 1898-1959) was a cooper by trade, and, like many of his contemporaries, he lied about his age in order to get involved in "the cause" and joined the Gordon Highlanders at the age of sixteen. After basic training he was shipped off to France where he suffered the horrors of life on the front line on the Somme. Many of his friends were killed or maimed. His brother, Davy, was gassed in the trenches and sent home after only a few weeks, but he, thankfully, came through his time at war relatively unscathed. My father told me he rarely spoke of his wartime experiences but had, at times, mentioned the disgusting, unsanitary squaller of trench life. Even in battle the lads wore the kilt and he told my dad how they used to run a candle flame up the pleats, when ever they had the chance, to kill off the lice and other "wee beasties" that had found a home there.

The contrast of experiences during the First World War could not have been greater for my grandfather and grandmother. Granddad, (George Sutherland, Peterhead, 1898-1959) was a cooper by trade, and, like many of his contemporaries, he lied about his age in order to get involved in "the cause" and joined the Gordon Highlanders at the age of sixteen. After basic training he was shipped off to France where he suffered the horrors of life on the front line on the Somme. Many of his friends were killed or maimed. His brother, Davy, was gassed in the trenches and sent home after only a few weeks, but he, thankfully, came through his time at war relatively unscathed. My father told me he rarely spoke of his wartime experiences but had, at times, mentioned the disgusting, unsanitary squaller of trench life. Even in battle the lads wore the kilt and he told my dad how they used to run a candle flame up the pleats, when ever they had the chance, to kill off the lice and other "wee beasties" that had found a home there.

In stark contrast, my grandmother (Ruby Watt, Crovie, 1898-1969) remembered much of the war as a time of adventure. Her life was typical of the girls of the north east coastal villages. She left the Bracoden school at 14 and got a job as a maid at nearby Troup House. Now a special school, but, at that time, the home of a well-to-do landowner. Aside from that, during the summer months, she worked with her sisters and cousins as a herring gutter, or "gutting quine", following the vast fleets of herring drifters from the far north down to Yarmouth with the hundreds of teams of girls who gutted and packed salt cured herring when the industry was at its height. But, when war broke out, the trade diminished quickly. Much of the demand for cured herring came from Germany, and that line of business, of course, had come to an abrupt halt. Only a small fleet of boats continued the fishing while many were commissioned by the admiralty for use as support vessels for the warships or as mine-sweepers. The huge numbers of gutting quines was no longer required so many of them sought work elsewhere. My grandmother and a few of her friends volunteered as land workers and were taken down to Deeside where they were trained to work in the timber mills as "barkers", stripping the bark off tree trunks before they were cut to shape for use as pit props in coal mines or shipped abroad for use in the trenches. She had warm memories of her time on Deeside, living with her pals in a deer stalkers' bothy and dining on fresh vegetables, salmon, trout and venison steaks. Saturday nights were the highlight of the week, when the gillies took the girls into Braemar on their motorbikes to enjoy a dance in the village hall.

In the winter of 1917 the girls were transfered to Dundee where they worked in a jute factory, making ropes for army tents. The picture below shows Ruby, second left, with her pals in Dundee in a studio pose typical of the time.

After the war my grandfather returned to work as a cooper. A couple of years later he got a job as fish buyer and yard manager for Fraserburgh curer, Abercrombie Davidson. One of his jobs, in the early spring, was to cycle along the coast as far as Gamrie, visiting the villages along the way to sign on 'gutting quines' for the herring season ahead. Those who signed on were given their arles, a small down payment on their wages. On one such occasion he signed on Ruby Watt, the young lass from Crovie who, a few years later, became his wife.

Gavin Sutherland, Peterhead.

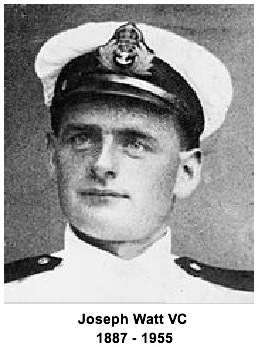

"Local Hero" Joe Watt, V.C. 1887-1955

On a May morning in 1917 the Gamrie herring drifter Gowanlea, having been commissioned by the Navy for wartime service, was one of a small fleet of boats on patrol in the Mediterranean Straits of Otranto when they came upon the Austrian light cruiser Novara. The events that followed led to skipper Joseph Watt, a Gamrie fisherman, being awarded the Victoria Cross.

The cruiser demanded that Watt surrender his boat but the skipper refused and ordered his men to open fire. The odds were hopelessly stacked against the eight man crew of the Gowanlea, an 87ft wooden drifter with a single deck mounted six pounder gun. The Novara was a 424ft armour-plated warship with a crew of over three hundred men.

With a cry of "Three cheers lads and let's fight to the finish!" Watt led his men into battle with the Novara. The great ship's guns blazed and almost instantly disabled the little boat's deck gun. Under intense fire the Gowanlea made a miraculous escape and later was involved in the rescue of several fishermen who's boats had been destroyed in the battle.

For his acts of "most conspicuous gallantry" Skipper Joseph Watt was awarded the Victoria Cross, Croix de Guerre and the Italian Silver Medal for Military Valour. Three of the crewman aboard the Gowanlea were awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.

Skipper Joseph Watt, Royal Naval Reserve.

For most conspicuous gallantry when the Allied Drifter line in the Straits of Otranto was attacked by Austrian light cruisers on the morning of 15 May, 1917. When hailed by an Austrian cruiser at about 100 yards range and ordered to stop and abandon his drifter the "Gowan Lea" Skipper Watt ordered full speed ahead and called upon his crew to give three cheers and fight to the finish. The cruiser was then engaged, but after one round had been fired, a shot from the enemy disabled the breech of the drifter's gun. The gun's crew, however, stuck to the gun, endeavouring to make it work, being under heavy fire all the time. After the cruiser had passed on Skipper Watt took the "Gowan Lea" alongside the badly damaged "Floandi" and assisted to remove the dead and wounded.

Joseph Watt, a modest, quiet man, returned to the fishing at the end of the war as skipper of the herring drifter "Benachie." Suffering from cancer, he died at his home in Fraserburgh in February, 1955.

The Great War As It Affected Peterhead.

Mary Findlay, The Links, Peterhead.

The Sunday prior to the declaration of war was a memorable day in Peterhead. The Naval Reserve, largely composed of fishermen, was called up, and there was much excitement and consternation as the contingent departed in two special trains. The 5th Gordon Highlanders mobilized at their Headquarters at the Drill Hall in Kirk Street, and the men were billeted throughout the town. The original battalion remained in Peterhead for a while and then transferred to Bedford for further training before going overseas.

An extensive Air Station was constructed at Lenabo from which Airships of various types patrolled the North Sea. There was a Seaplane Station at Loch Strathbeg, and another was commenced in the South Bay, near the Prison, but was not completed when the war ended.

During the War telegraphic communications between The British Government and Russia were maintained through Peterhead, and it is interesting to note that the first news of the Revolution came to Great Britain through the Geddle Braes in March 1917.

The Rescue Hall, in Prince Street, was converted into a Red Cross Hospital and volunteers under Colonel Masson and Doctor Carmichael of Boddam served by carrying the wounded from the train to the ambulance wagon, and from the wagon to the hospital. More than 600 men were cared for at the hospital.

During the War several vessels were sunk by mines not far from the port, and the landing of torpedoed crews was a common occurrence. One Saturday evening in August, 1915, a German Submarine crew was landed in Peterhead. Some of our fishing boats had been ruthlessly sent to the bottom the previous day and the feelings of the people were stirred. Their submarine had been attacked and destroyed in a planned attack, using a fishing boat as a decoy which was accompanied, from a distance, by a number of armed trawlers. When the U-Boat surfaced to attack the fishing boat the trawlers struck a lethal blow when a shot hit the conning tower killing the Captain and destroying the boat. The crew surrendered when they realised their boat was now a wreck. Six officers and twenty-one men were captured that day, and great was the excitement as they were marched up Broad Street to the Drill Hall. They were later taken south to a prisoner of war camp.

Through the years of the war the lighthouses along the coast had been forbidden to be lit. No street lamps were lit and all windows were blacked out. No lights on land or sea. Even the church bells were forbidden to be rung on a Sunday morning, but, with the end of the War came the ringing of bells and great rejoicing. Although, in outward appearance, Peterhead had not suffered much from the War, in many homes there were sorrowing hearts and blanks that could never be filled.

Extracted from "A History of Peterhead", James T. Findlay, 1933.